Crafting a Storm Surge and Hurricane Risk Rating for Coastal Properties

In an era where climate change is intensifying the frequency and severity of storms and hurricanes, especially in coastal regions, understanding and quantifying the associated risks is critical.

According to the National Geographic Society, a storm surge is a rise in sea level that occurs during tropical cyclones, which are intense storms also known as typhoons or hurricanes.

The storms produce strong winds that push the water into shore which can lead to flooding and pose a real threat in coastal regions.

To help understand these risks, a Storm Surge and Hurricane Risk Rating score can provide property owners, developers, real estate agents, insurers, urban planners, local governments, buyers and investors with a clear picture of a property’s vulnerability to these natural disasters.

These stakeholders will be conducting their own necessary research, and a risk rating system can offer an indicative metric to guide their decisions.

Why is a Storm Surge and Hurricane Risk Rating Important?

Understanding storm surge and hurricane risks is crucial for building a resilient society.

Natural catastrophes pose significant challenges, and quantifying these risks can aid in better preparation and prompt responses.

Strengthening homes and incentivising homeowners to invest in property fortification can reduce potential losses. Accurate risk assessments and reliable data can allow insurers to offer discounts for mitigation actions, enhance home resale values, and reveal the increased costs to mortgage issuers due to natural disasters.

Achieving resilience relies on expert understanding of the real estate ecosystem and the benefits of informed mitigation strategies.

Steps to build a Storm Surge and Hurricane Risk Rating

1. Defining scoring criteria and scale

The foundation of a risk rating system is a clear and understandable scale, such as 1 to 10, with each number representing a different level of risk.

Establishing specific criteria for assessment is also essential for a well-rounded evaluation.

2. Key factors to consider

Several factors contribute significantly to a property’s risk from storm surges and hurricanes:

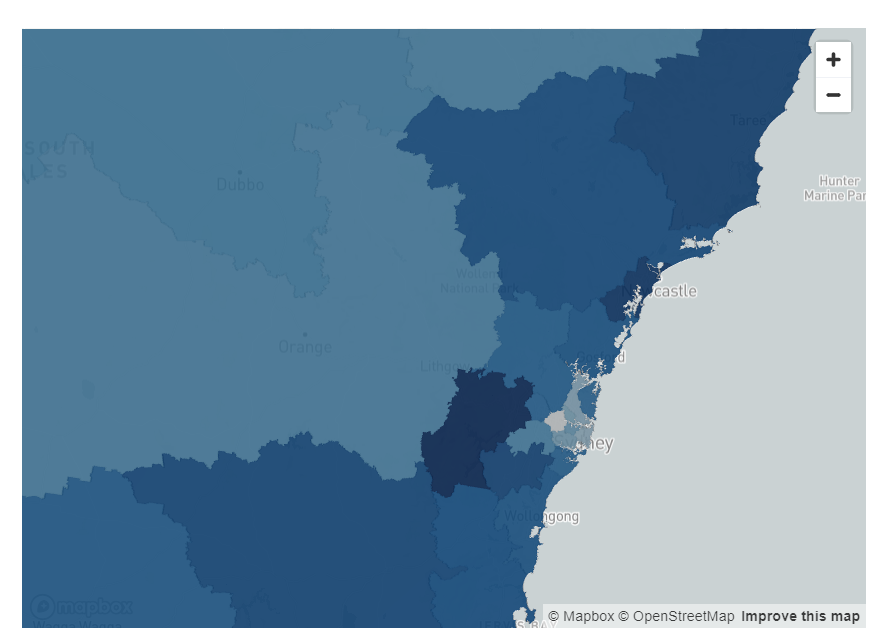

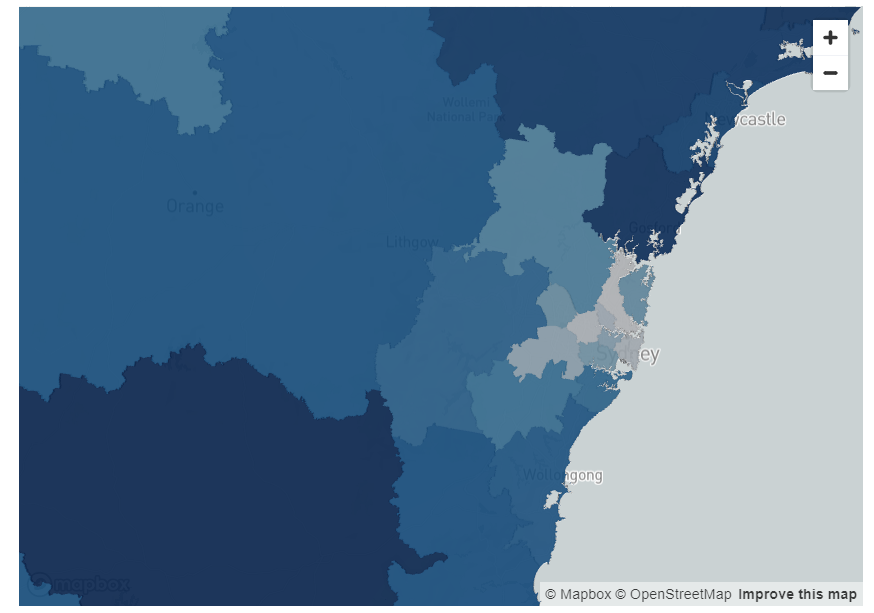

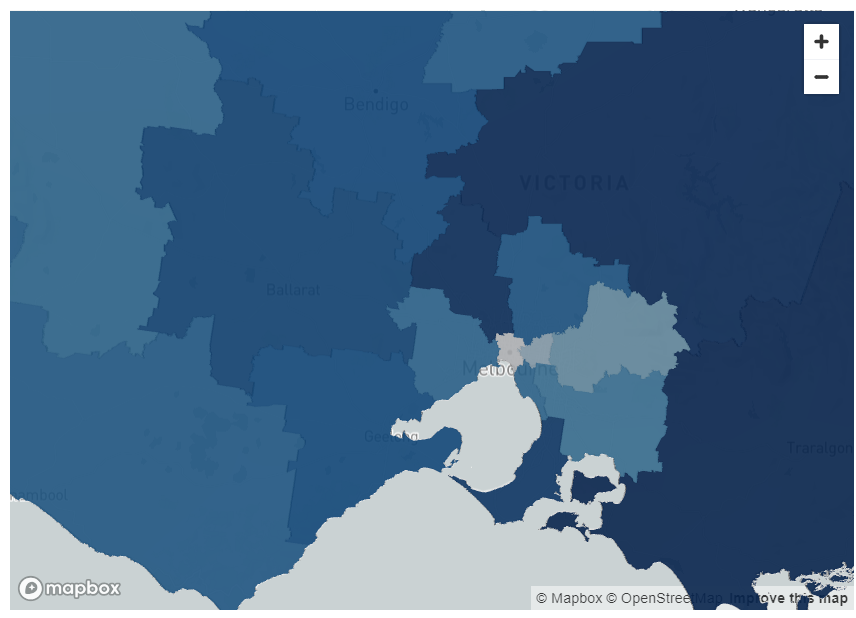

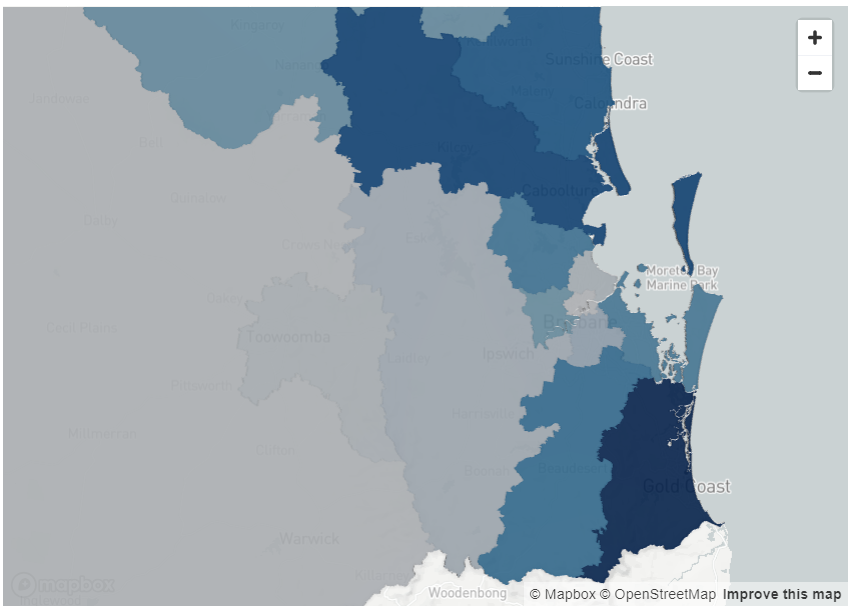

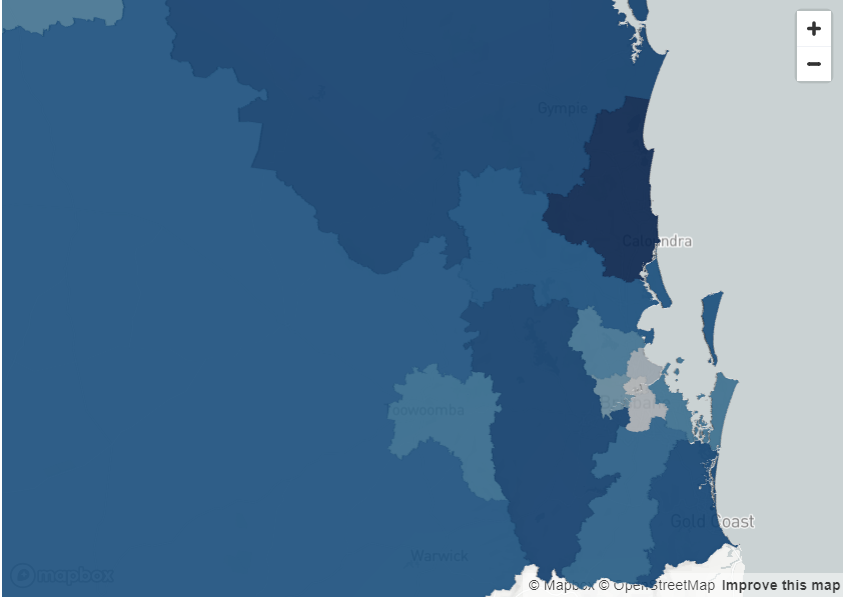

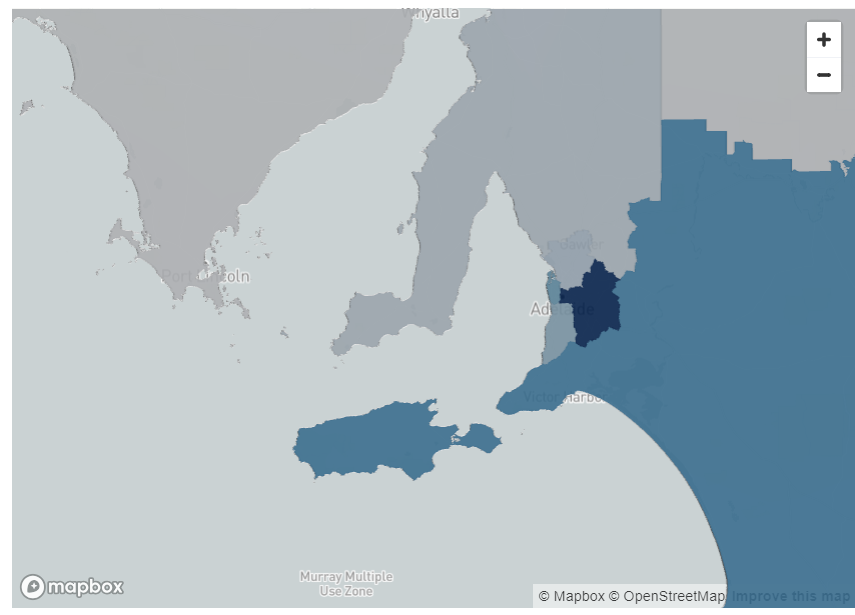

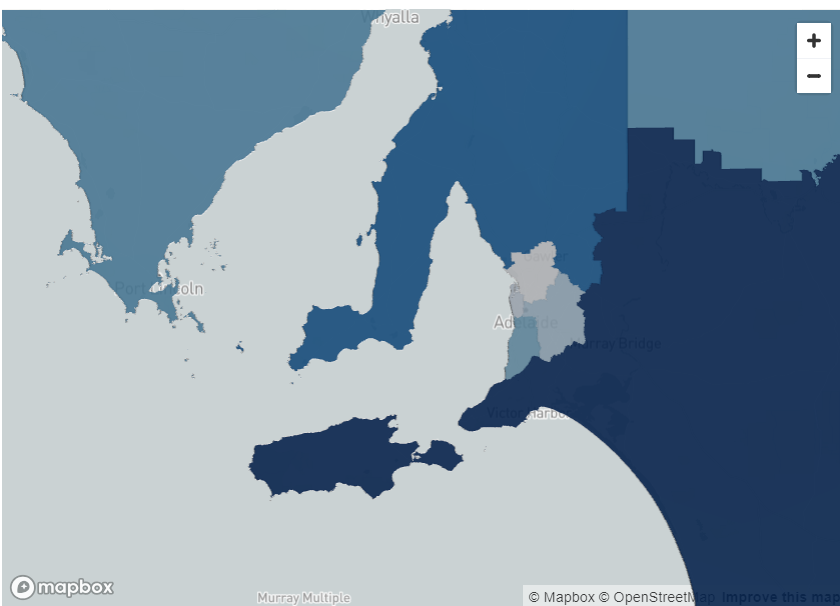

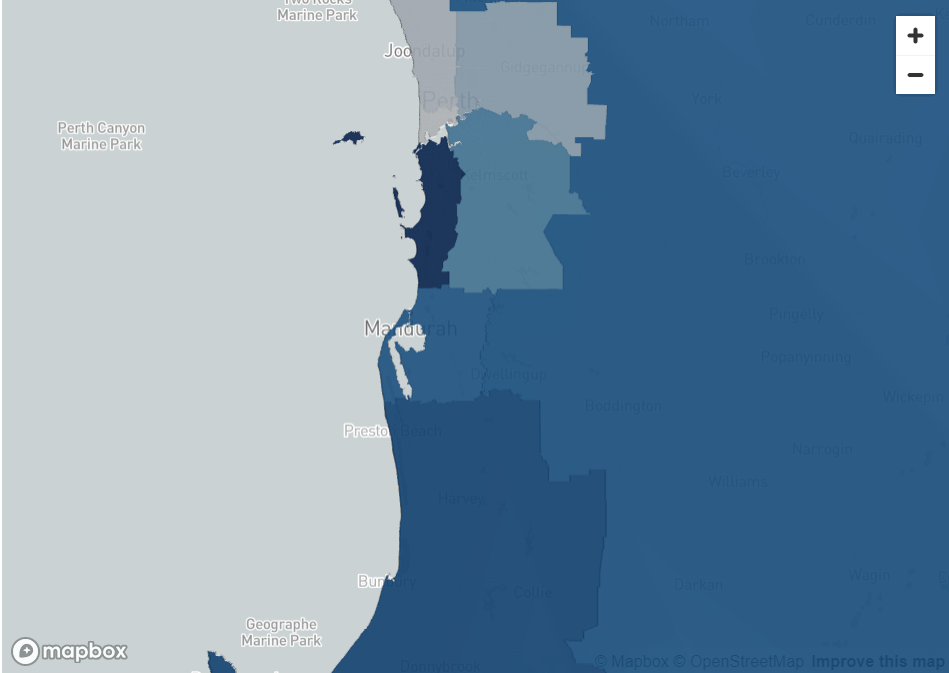

- Proximity to Coastline: The closer a property is to the coastline, the higher the risk of storm surge impacts.

- Elevation and Topography: Properties at higher elevations or with certain topographical features may have reduced risk.

- Historical Data: Analysing past hurricane and storm surge incidents from historical weather databases and local government records can provide critical insights into potential future risks.

- Local Climate Trends: Understanding the local weather patterns can help predict the likelihood of storms.

- Flood Zone Designation: Properties in designated flood zones face a heightened risk. Flood risk information is generally available from Local Councils.

- Building Design and Materials: Construction that is designed to be resilient against high winds and flooding can mitigate risk.

- Infrastructure and Preparedness: Robust local infrastructure and emergency plans can play a vital role in risk reduction.

- Natural Barriers: The presence of natural features, such as dunes or wetlands that can absorb storm impacts, reduces risk.

- Regional Planning: Effective community and regional planning and zoning can mitigate potential damage. Consult local zoning laws and development plans for more property-specific.

3. Assigning weights to each factor

Assigning appropriate weights to each of the above factors based on its impact on overall risk ensures that the score accurately reflects the property’s vulnerability.

Use expert consultations and statistical analysis to determine appropriate weights, and adjust weights based on real-world data and expert feedback.

4. Data collection and analysis

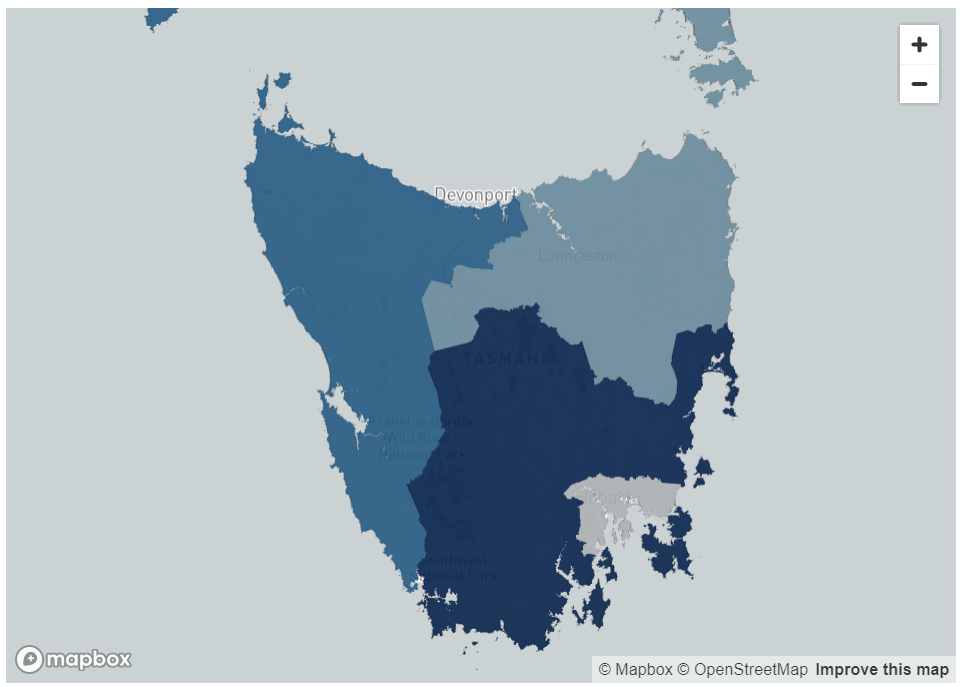

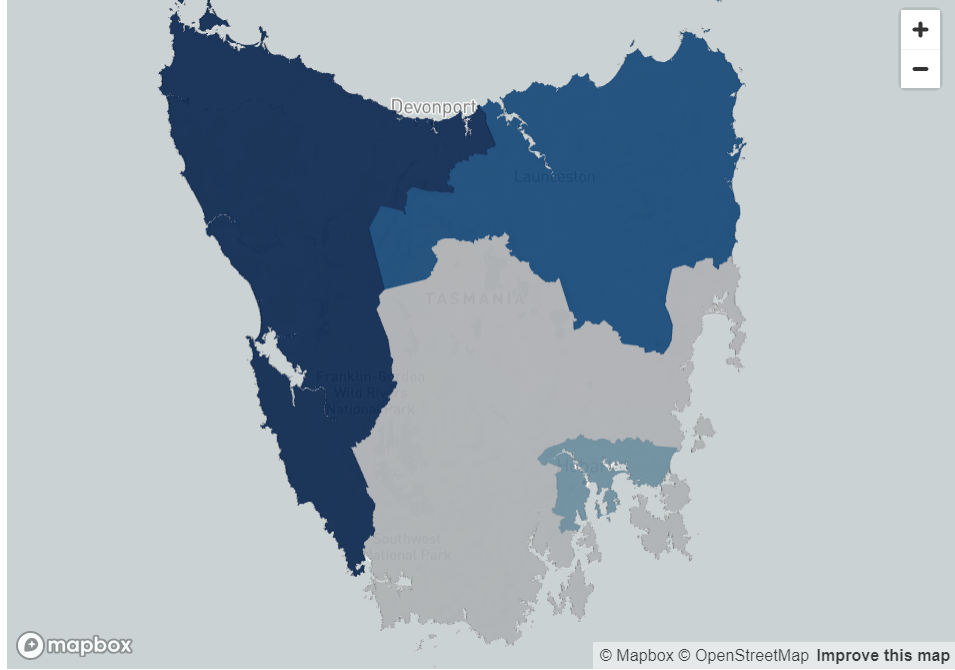

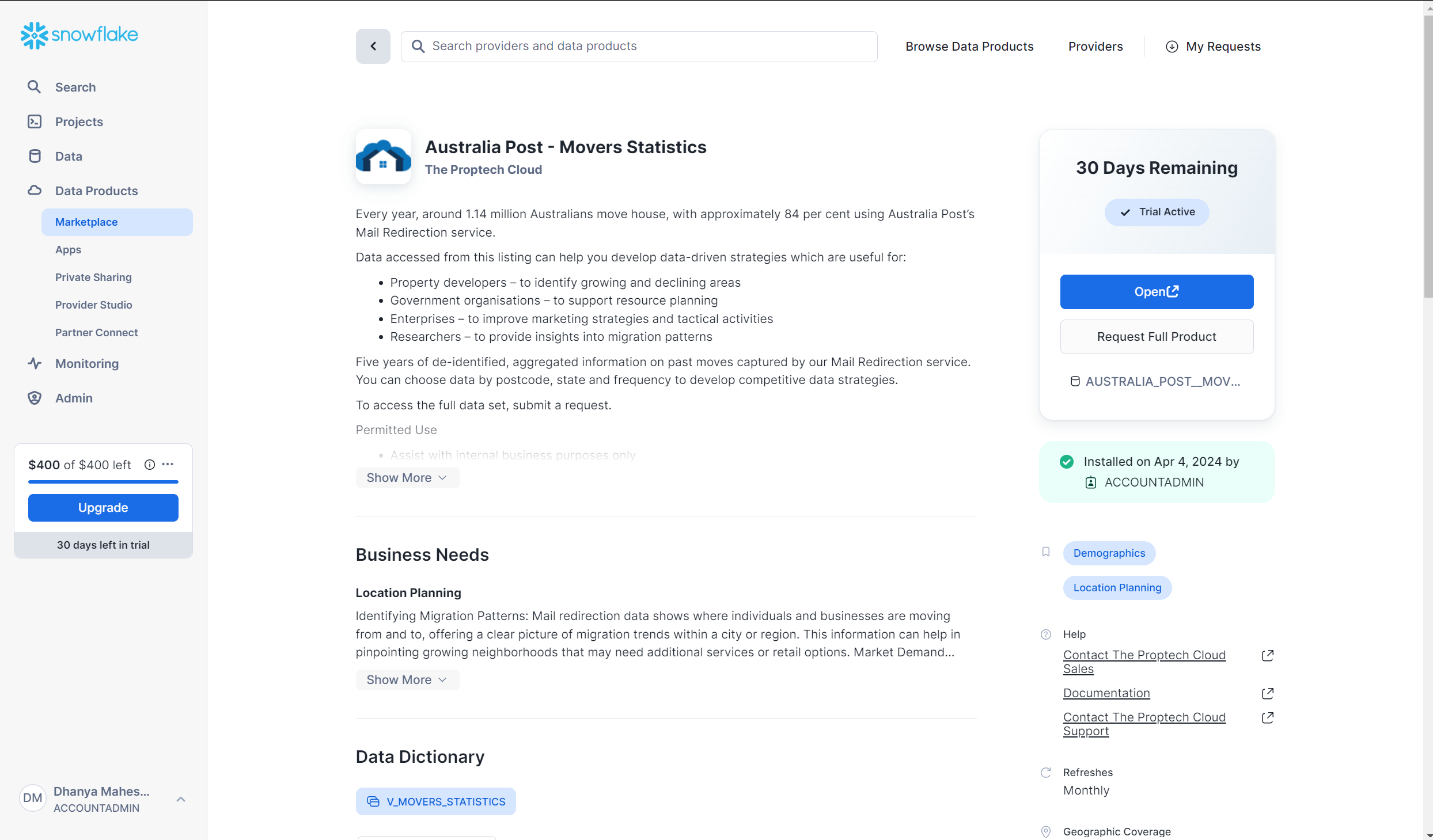

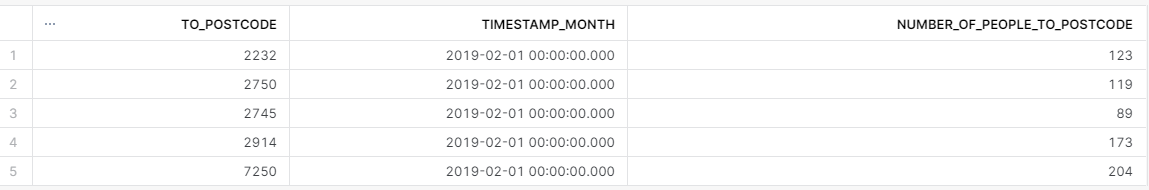

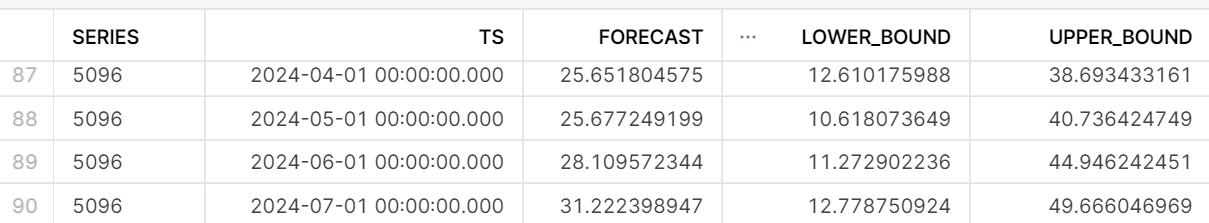

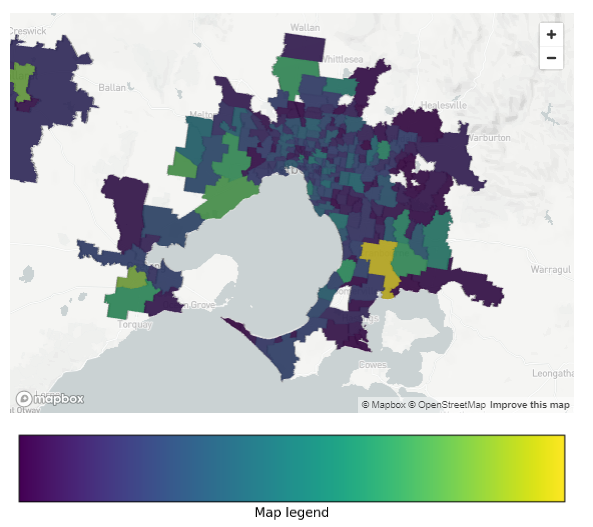

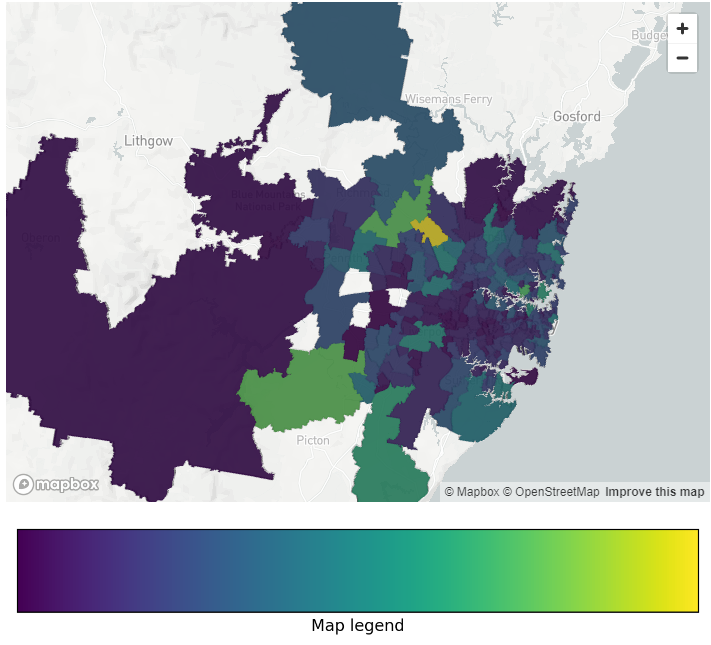

Gathering and analysing data, including GIS mapping, climate records and historical event data, is crucial to assigning accurate sub-scores for each criterion. Cross-referencing multiple sources will ensure data accuracy and statistical software can be used for thorough analysis.

5. Calculating the overall score

By aggregating these sub-scores, considering their respective weights, we arrive at a comprehensive risk rating for each property. Using a formula or algorithm will ensure consistency in calculations. Further validating the scoring system with sample properties will help improve accuracy.

6. Validation and adjustment

It’s vital to validate and adjust the rating system against historical data and expert analysis to ensure its reliability and accuracy. Regularly review and update the criteria and weights based on new data.

7. Providing risk mitigation recommendations

Along with the risk score, offering advice on how to reduce a property’s vulnerability to storm surges and hurricanes can be highly beneficial. Suggestions such as upgrading building materials, improving drainage systems or investing in flood barriers can form a checklist of actionable steps to reduce a property’s vulnerability.

8. Regular updates and re-evaluations

Continuously updating the risk rating system to reflect environmental changes, infrastructure developments and updated data is crucial. This includes regular reviews, incorporating new data and tech advancements can improve the risk rating system.

Building Resilience with Accurate Risk Ratings

Stakeholders can create a robust and reliable risk rating system that enhances safety and preparedness in coastal areas.

A well-developed Storm Surge and Hurricane Risk Rating can provide essential information for making educated decisions about property development, insurance and risk management.

As the world grapples with the increasing challenges of climate change, these tools become ever more critical in our collective efforts to build resilient communities.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Subscribe to receive the latest blogs and data listings direct to your inbox.